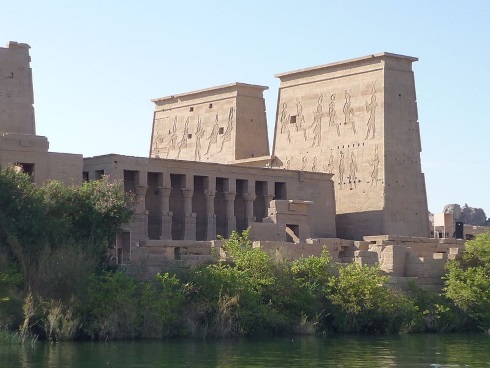

Even as ruins, the palaces and temples that sit astride the Nile at cities such as Thebes, Memphis and Heliopolis can still amaze. Their stones and hieroglyphs are testament to the ambition, sophistication and continuity of the civilisation that built them. In the Valley of the Kings lie more wonders, the burial places of royalty from time immemorial. The first dynasty of ancient Egypt was established more than three thousand years before the birth of Christ. Its thirty-one successors held sway until the coming of the Romans and the dawn of the Christian era. At its high point, the Egyptian Empire stretched from Sudan in the south to the borders of Turkey in the north. Tribute from conquered peoples and allies made Egypt rich and self-confident. The attainments of her building projects are astounding for any epoch. The Great Pyramid of Cheops (Khufu), standing just over 480 feet high and for over four thousand years the tallest structure on earth, was crafted by a people who had neither iron, nor wheel, nor capstan, nor pulley. It reputedly holds enough stone to build a wall ten feet high and five feet wide from Calais to Baghdad. For this to have been constructed by a society without modern technologies is almost beyond comprehension. Not surprisingly, Egyptians were proud of their heritage and valued the old ways.

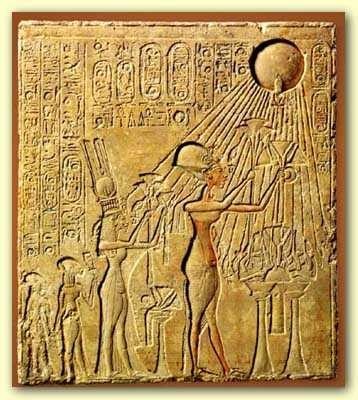

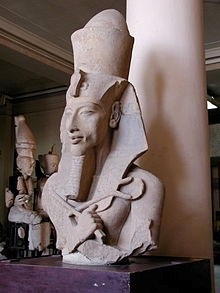

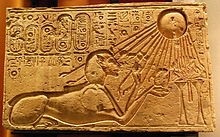

Yet in the fourteenth century BC, towards the end of Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty, something quite remarkable happened. Centuries of tradition were overturned. A new ruler compelled the court to quit the ancient capital for a metropolis built from scratch on the edge of the desert. Leaving behind the treasured places of his forefathers and moving to virgin land was deeply symbolic, but greater upheavals were to come. This same pharaoh signalled a change of spiritual allegiance by altering his name, turning his back on the old pantheon of gods and instituting novel forms of worship. He promoted radical and innovative art forms so shocking in their representation of the human body that some believe they indicate hereditary disease in the royal family. There appears to have been a period of national self-absorption or introspection that left the country largely paralysed in the face of military and political threats from beyond its north-eastern borders. Most revolutionary, divisive and cataclysmic of all for a people steeped in polytheism, this monarch insisted on worship of one god above all others. By the time the seventeen years or so of his reign had passed, Egypt was in turmoil, her old ascendancy abroad vanished. She was never to recover her former hegemony fully.

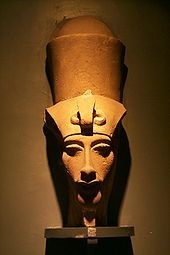

The man who did these things was Akhenaten – so reviled by later generations that he was called “criminal”, “rebel” or “enemy”, his name deliberately omitted from the king lists which were recited to ensure nourishment to the departed in the afterlife. The aim was no less than to bring about the personal obliteration of a man whose very memory was anathema, for Egyptians believed that only through such commemoration was rebirth possible. Within a short space of the heretic’s passing Thebes was again the capital and temples to the old gods had been re-opened. There followed a self-conscious national act of forgetting that attempted to erase all trace of this unique experiment. What had brought it about?